[Updated 27June, 4 August 2021]

The early view that the continent of Africa had been “spared,” relative to the Global North, in the coronavirus pandemic is debunked by emerging data. While known infection rates and death rates are lower, many countries – including South Africa – have entered a third wave, and with global inequities in vaccine access deeply entrenched, ongoing impacts will be felt for a long time to come.*

The growth and spread of new variants of COVID-19 in the absence of vaccination is a major concern across the continent, and by extension the world. As the World Health Organization’s Regional Director for Africa, Matshidiso Moeti, recently said, “It is crucial that we swiftly get vaccines into the arms of Africans at high risk of falling seriously ill and dying.” Troublesome Beta and Delta variants are circulating in many African countries, and in light of low testing levels in some regions, the emergence of other variants may go undetected until they become widespread.

A wide range of statistics paint a grim picture of global vaccine inequity. Only 0.3% of the more than 800 million doses administered by the end of April went to people in lower-income countries. While the US gives 3 million jabs per day, fewer than 40 million had been administered by May, in total, across 100 countries of the Global South. G7 countries outpaced low-income countries in vaccination 73:1. While two-thirds of Canadians were at least partially vaccinated, less than 1% of the population of low-income countries had received a dose. Canada has been widely seen as a “hoarder,” reserving up to five times as many doses as we need, while COVAX – the global mechanism for equitable vaccine access – is grossly undersupplied. By August 2021, the proportion of vaccinated in lower-income countries had risen only 0.5 percent, to 1.5 percent, mainly due to lack of supply. Meanwhile wealthy countries were proposing to consume yet more of the world’s supply through booster shots.

Two weeks ago COVAX put out an urgent call to rich-country governments, noting that it faces a second-quarter shortfall of nearly 200 million doses – mainly because of the need in recent months to prioritize delivery to South Asia as the catastrophe unfolds there. Donor nations must prioritize access to vaccines before such devastating surges occur. COVAX calls on the G7 and other wealthy nations to “urgently unlock new sources of doses, with deliveries starting in June, and funding so we can deliver.” COVAX has the infrastructure and expertise to manage this global effort. It needs the vaccines. Twenty-six African countries have exhausted their COVAX supply or are about to run out. Malawi ran out just as thousands were due for second dose.

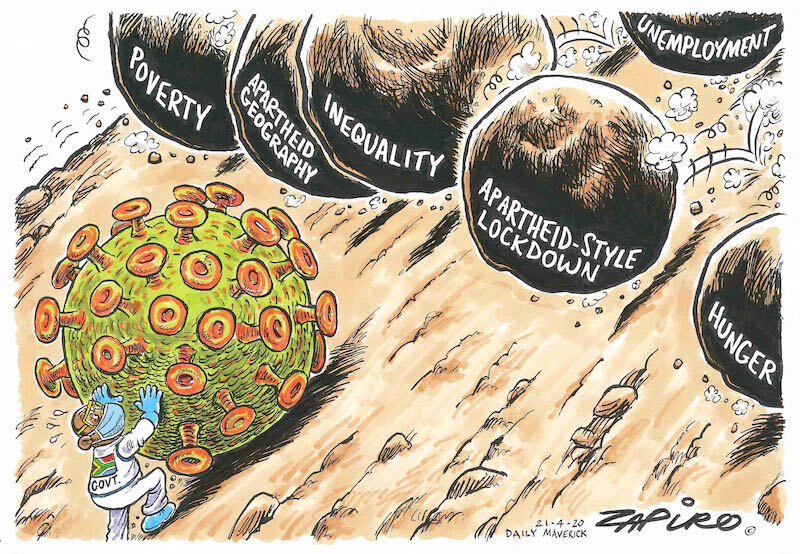

My friend Mixo M, a nurse from N’wamitwa who works at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Johannesburg – the largest hospital in the Southern Hemisphere, and the inner-city hospital at the epicentre of Gauteng Province’s surging third wave – has only recently received her jab. Mixo’s situation as a worker truly on the frontline of South Africa’s pandemic is emblematic of inhumane, and dangerous, global supply inequities. (The country, which has now vaccinated about 3% of the population [4.8% by late July], was lauded for an effective early response. It has since faced an array of hurdles, including very slow delivery by COVAX, a government scandal, and a dominant variant that didn’t respond well to the Astra Zeneca vaccine the government initially prioritized and then sold off.) As Dr. Keitumetsi Sothoane of the same hospital puts it, “Our biggest worry as health care workers [is] the impact of the virus on our already understaffed, overburdened, overwhelmed, and resource-limited public health care system.” The head of the country’s medical association says bluntly that while they managed previous waves, this time hospitals cannot cope. The longer the country waits to be vaccinated, the greater the strain on that system. Beyond public health, it is hard to fathom the potential long-term economic and social impacts of a protracted pandemic in a country that already ranks as the most unequal on earth.

This week’s G7 summit in England failed to take the resolute action needed to improve global vaccine access, mainly due to an unwillingness to confront the interests of Big Pharma. Oxfam UK issued a sharp rebuke at the close of the summit:

“[G7 leaders] say they want to vaccinate the world by the end of next year [2022], but their actions show they care more about protecting the monopolies and patents of pharmaceutical giants.” Sharing a billion vaccines, as G7 nations have pledged to do, is an important step — but the WHO says it needs 11 billion to reach its (lofty) goal of 70% global vaccination by this time next year. The G7 donations pledge “will only get us so far,” Oxfam says. “[W]e need all G7 nations to follow the lead of the US, France and over 100 other nations in backing a waiver on intellectual property. By holding vaccine recipes hostage, the virus will continue raging out of control in developing countries and put millions of lives at risk.”

“Wanting” to vaccinate the world by the end of 2022, without action, is pretty words: most projections are that poor nations will wait until 2024 for full vaccination. Pharmaceutical companies hold the lucrative patents, blocking the ability of countries like South Africa to undertake their own, local production of vaccines and other medicines needed for the COVID response, or even to direct their own import programs. Much of the research that grounds vaccine development was publicly funded over many years, and governments transferred more than US$110 billion to pharmaceutical firms to finance urgent research and roll out of COVID vaccines. Yet the powerful companies – enabled by patents – monopolize production, keep prices high, and keep out-size profits flowing.

Pharmaceutical companies claim that Global South countries don’t have the skill or latest technologies needed to produce their own COVID-19 vaccine, a colonialist view that is simply wrong (as both India and South Africa have demonstrated). South Africa and India first requested a waiver of certain World Trade Organization intellectual property rights in October 2020, to enable countries to direct their own vaccine programs. More than two-thirds of World Trade Organization members have signed on to the waiver proposal. Canada has not signed on to this important step in removing barriers to wider, more equitable vaccine production and access.

Economist Joseph Stiglitz calls the patent waiver “a critical first step” to ensure optimal global access to vaccines and other therapeutics for COVID-19 – for the sake of both public health and economies. “There is no way to beat COVID-19,” he emphasizes, “without increasing vaccine production capacity. And some production must be in the Global South for a host of reasons, including that prompt suppression of new variants is how we avoid more deaths and quarantines.”

For Southern Africans, glaring inequities in access to life-saving medical therapies raise disturbing memories. The world watched (or, more aptly, turned a blind eye) while HIV/AIDS completely overwhelmed the healthcare systems of countries across Southern Africa and ravaged a generation. It certainly needn’t have happened: South African civil society organizations, spearheaded by the Treatment Action Campaign, had launched a high-visibility campaign for equal access to life-saving anti-retroviral medications by 1998. Yet the pandemic of HIV/AIDS peaked in Southern Africa in 2005-06, fully a decade after most Americans, Canadians, and others in the North had access to the ARVs that transformed HIV from a death sentence to a manageable chronic disease. The speed of developing the new medications (which was impressive, though laggardly when compared to the lightning speed of COVID vaccine development) “was not matched by a similar speed in ensuring everyone could get access to the [medications], with treatment out of the reach of the global poor,” says Deborah Gold of the UK’s National AIDS Trust. Pharmaceutical patents were a hurdle then too. It took dogged activism by groups like the Treatment Action Campaign to finally prick the conscience of wealthy nations, multilateral institutions, and pharmaceutical companies. These groups’ voices, and the voices of African grandmothers who played such a central role in the AIDS response at community and household level, were amplified by Stephen Lewis, then-UN Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS and himself one of the most dogged figures working to marshal local and global resources in the struggle against HIV/AIDS.

Still today, grotesque inequities in access to HIV treatments persist. This is a mark of a major failure in global political will and resource provision.**

Deborah Gold speaks of striking parallels in official responses to HIV and to Sars-CoV-2. A nation-by-nation approach fuels vaccine nationalism and more inequity, and can hardly succeed against a virus coursing through the veins of the world. Among the similarities in response: “governments being too slow to respond; a marked impact on minority communities and a failure to understand why; a governmental response which has veered into overpolicing and victim-blaming, rather than taking every conceivable measure to help people stay safe and healthy.” Another: pharmaceutical companies more concerned about proprietary knowledge and profit than anything like a human right to health. The history of the global response to HIV teaches myriad lessons, many of them simple: the more people treated quickly, the better people’s health, the fewer who are able to pass on the virus, and the fewer who fall ill and become a burden on health care systems.

The coronavirus pandemic is an opportunity for the global community to act like a community, considering the interests of all before (or at least alongside) the interests of each. Instead we seem to be treating vaccination like “a league table,” as Gold puts it, a competition to see which country gives the most jabs first, which company rakes in the biggest profits. Once again, the former colonies in the Global South are stuck in the waiting room.

___________

*Africa, the continent, sits at just over 130,000 recorded COVID-19 deaths thus far [early June], putting the continent sixth for death toll behind the US, Brazil, India, Mexico, and Peru. Numbers of dead are known to be underestimates in many countries, including these five.

**HIV/AIDS is far from a thing of the past. 38 million people currently live with HIV worldwide (35 million have died since the start). While new infections have fallen dramatically due to medical treatments, in 2020 1.5 million new cases of HIV were recorded, nearly 900,000 of them in Africa – where adolescent girls are hardest hit. Access to life-saving medication, which also suppresses transmission, continues to be a struggle for millions of poor and marginalized people worldwide, and pandemic shutdowns have deepened the challenge in ways that are not yet clear.

Sources include –

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe. Princeton University Press, 2000.

COVAX Joint Statement. “Call to Action to Equip COVAX to Deliver 2 Billion Doses in 2021.” World Health Organization, 27 May 2021.

Gold, Deborah. “’Vaccine Nationalism’ Echoes the Disastrous Mistakes Made with HIV.” The Guardian 2 Feb. 2021.

Grandmothers Advocacy Network [Canada]. COVID-19: Resources. grandmothersadvocacy.org/issue/covid-19-vaccines-testing-and-treatments

Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre. COVID-10 Map [13 June 2021, 30 July 2021] coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

Oxfam UK. “Reaction to G7 Communique.” 13 June 2021. www.oxfam.org.uk/media/press-releases/reaction-to-g-communique/7

Stiglitz, Joseph and Lori Wallach. “Preserving Intellectual Property Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccines is Morally Wrong and Foolish.” Washington Post 26 April, 2021.

Trade Justice Network. “Canada, Global Vaccine Inequality, and TRIPS Waiver.” 10 May 2021.

UN AIDS. Global HIV and AIDS Statistics [2020]. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf

World Health Organization. Director General’s opening remarks at Aug. 4 briefing. 4 Aug. 2021. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-4-august-2021

One of many powerful sentiments expressed at this year’s South African conference on Recognition, Reparation, and Reconciliation is “we wanted freedom, and we got democracy.” The frustrations of young people in particular, nearly a quarter century after the hard-won achievement of democracy, are deep and deeply warranted. There is no meaningful freedom for youth (here defined as under 35) who cannot find jobs, even if they were fortunate enough to finish high school and access some form of higher education. Nor is there meaningful freedom for older women who now earn a monthly income from the Old Persons Grant – only to exhaust every cent of it helping to support two or three generations of family members.

One of many powerful sentiments expressed at this year’s South African conference on Recognition, Reparation, and Reconciliation is “we wanted freedom, and we got democracy.” The frustrations of young people in particular, nearly a quarter century after the hard-won achievement of democracy, are deep and deeply warranted. There is no meaningful freedom for youth (here defined as under 35) who cannot find jobs, even if they were fortunate enough to finish high school and access some form of higher education. Nor is there meaningful freedom for older women who now earn a monthly income from the Old Persons Grant – only to exhaust every cent of it helping to support two or three generations of family members.